Not mentioned in one of my earlier posts while in New Orleans, was that after שחרית (morning prayer service) that day, the Chabad rabbi went around asking if anybody wanted to put on תפילין (tefillin), as there were some college students around, some of whom had just arrived for breakfast and who hadn't davened (prayed) yet. While going around, my sister said she would, but that's not for what the rabbi was asking. She further noted that he had been asking if "anybody" wanted to put on tefillin, though she pointed out that he ought to be saying "any men", since he probably wasn't going to give it to any women (for more on Chabad's perspective and discourse on women not wearing tefillin, see askmoses.com). I then offered my sister mine, which was met by her response that she's not going to put on tefillin until she knows more about the subject. Thus this posting (I am not here dealing with the issue of girls putting on tefillin in school, but rather women in general.).

The discussion largely begins with a mishnah in the third chapter of Berakhot:

The reason that they are exempt is due to their exemption from all positive time-bound commandments (as they are worn neither on shabbas nor on holidays, there is a time element to them), which would mean that it's not that they are forbidden to perform such מצות (commandments), but that they don't have to [and can perform them if they so choose].נשים ועבדים וקטנים--פטורין מקרית שמע ומן התפילין, וחייבין בתפילה ובמזוזה ובברכת המזון.Women, servants, and children are exempt from the reading out of the Shema and from [wearing of] tefillin, but are obligated with prayer, mezuza, and with the grace after meals.

The main argument that was put forth against women putting on תפילין (tefillin) is that put forth by the sixteenth century sage Rabbi Yosef Karo (in his Beit Yosef) (and the Tosafist(s) that he quotes):

Where the idea comes that is mentioned in the Tosafot that women are not careful about having a clean body is quite strange. In our times, women are cleaner than men; if anything, it should be that men are not careful enough to keep clean bodies (!). Thus, how can one say that women cannot wear tefillin due to lack of bodily cleanliness?בית יוסף אורח חיים סימן לחA mishneh in chapter "Who's dead..." (ch. 3 in Berakhot), the [stam] gemarra (Berakhot 20a) gives the reason that it's because it's a positive time-bound commandment, and women are exempt from all positive time-bound commandments. And Rabbi Asher, son of Yehiel wrote in the laws of tefillin (section 29): "Even though we have established like Rabbi Akiva, who said, 'Night is a time of tefillin' (Eruvin 96a), shabbasos and holidays are not times of tefillin. [The author of the] Kol Bo wrote (in section 21) in the name of the Ram (?), 'that if women want to put on tefillin, we don't listen to them because they don't know how to guard themselves in cleanliness.'" And in the book Orhot Hayyim (laws of tefillin, section 3), asks on what is said in the beginning of the chapter "The one who takes out tefillin..." (also on Eruvin 96a) that 'Mikhal, daughter of Kushi, wore tefillin and the sages did not reprimand her.' And to me it seems that the reason of the Ram is like the Tosafot have written (Eruvin 96a, s.v. "Mikhal") that in the Pesikta [Rabbati] (chapter 23) that the sages did reprimand her. And they (the Tosafists) explain that the reason is that [wearing] tefillin requires [one to have] a clean body, but women are not zealous to be careful. And the Ram wanted to suspect [to be careful] to the words of the Pesikta.

ונשים ועבדים פטורים. משנה בפרק מי שמתו (ברכות כ.) ויהיב טעמא בגמרא משום דהוי מצות עשה שהזמן גרמא וכל מצות עשה שהזמן גרמא נשים פטורות. וכתב הרא"ש בהלכות תפילין (סי' כט) ואע"ג דקיי"ל כרבי עקיבא דאמר (עירובין צו.) לילה זמן תפילין מכל מקום שבת ויום טוב לאו זמן תפילין: כתב הכל בו (סי' כא) בשם הר"ם שאם רצו הנשים להניח תפילין אין שומעין להן מפני שאינן יודעות לשמור עצמן בנקיות עכ"ל ובספר ארחות חיים (הל' תפילין סי' ג) הקשה עליו מדאמרינן בריש פרק המוצא תפילין (שם) דמיכל בת כושי (פירוש בת שאול) היתה מנחת תפילין ולא מיחו בה חכמים. ולי נראה שטעם הר"ם כמו שכתבו התוספות (ד"ה מיכל) דאיתא בפסיקתא (רבתי פרק כב) שמיחו בה חכמים ופירשו הם דטעמא משום דתפילין צריכין גוף נקי ונשים אינן זריזות ליזהר והר"מ רצה לחוש לדברי הפסיקתא:

Nevertheless, in his Shulhan Arukh, he didn't try to prevent women from wearing them (OC 38.3: "Women and servants are exempt from [wearing] tefillin, because they it is a positive time-bound commandment."), only saying that they were exempt from wearing them. However, his contemporary, Rabbi Moses Isserles, glossed there that "but if women want to be stringent upon themselves, we reprimand them."

As to why Rabbi Isserles opined in such a fashion, it seems that it was due to the cleanliness concern (see the ט"ז, מ"א, & מ"ב who all opine that that was his reasoning). However, the wording of stringency pointed to as being the reason that women ought to be reprimanded seems like the crux of the issue for Rabbi Isserles. It may be due to the concern that if women think that the wearing of it is a stringency, that it is an erroneous line of thinking.

Alternatively, it seems that there is a cultural concern here. Such that, halakhically, it's fine to do a מצוה (commandment), however, it strikes men in such a way that it just doesn't jive with their sense of society (this was briefly brought up in On the Main Line). This is largely similar to the idea that tefillin and tzitzis are distinctly men's garments, which is an interesting argument (keep in mind the famous aphorism that "Clothes make the man," thus indicating that clothing is a social marker, and that it is something that is culturally-contingent), though according to the Bible, that is not so - it is only through rabbinic midrash that one learns of women's exemption from these commandments, but neither their inability to perform them, nor of their sense of being garments singled out for men only (if one even sees tefillin as being a garment in the Torah, but that's not important for this discussion).

Nevertheless, I think it's important to be sensitive to one's environment (yes, this concept arose in my mind through the conversations we had about women and tefillin in yeshiva). If one is in a place where it makes people (not just men, maybe also women) uncomfortable or is against the customs or comfortability of a place, it may be an issue to the extant that it is not something to which people are accustomed and be a statement of some sort with which those people or places are not okay.

So, I think I would say that it would be okay for her to wear tefillin if she wanted to, though she ought to be careful at Chabad, as it may go against their understanding of gender distinctions.

(A couple of blog postings are worth a read on this topic: On The Fringe and Barefoot Jewess.)

24 comments:

very interesting...not to make light of the subject, but i never knew that the pictured individual was a lefty...

now what about a tallis, or say, kippah, for this subject, as i've heard/seen some people do?

where did you get the second photo on the post (the black and white one)?

tnspr569,

They are each different. Tallis is fairly similar to tefillin as it is also a mitzvah, but I'm not planning to go into that here. Kippah is a different story as it has no mitzvah significance and is mainly identified as a something that men wear, so it's a lot more difficult to make the argument that women can wear kippot than it is for either tallis or tefillin.

aaa,

The black and white photo is from the Barefoot Jewess post that is linked the bottom of my posting.

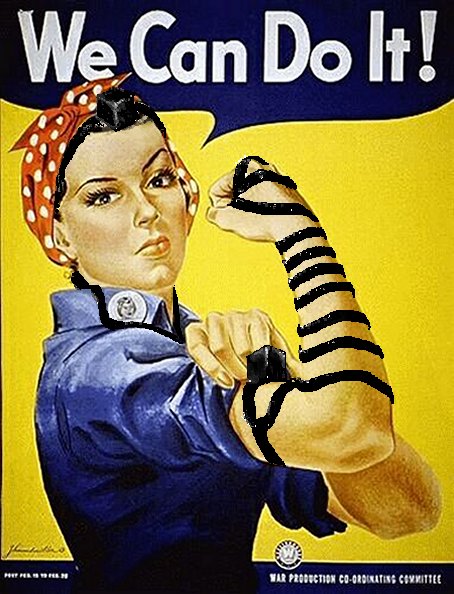

also, the Rosie the Riveter picture with tefillin is from somewhere on http://sospire.blogspot.com

"though according to the Bible, that is not so - it is only through rabbinic midrash that one learns of women's exemption from these commandments"

There you go again, seperating the written text from its oral context as if the latter is somehow less Divine.

I also found curious your statement that "though according to the Bible, that is not so - it is only through rabbinic midrash that one learns of women's exemption from these commandments."

Are you implying that according to Torah law women ARE hayyavot in mizvot aseh sh'Hazeman geraman???

Anonymous,

Yes, I am separating the text of the Humash from the rabbinic interpretations of it - it's how it works. If we didn't have midrashim, we would be Karaitic or whatever - it's through the rabbinic system which we follow for halakhah.

The idea of women being exempt from positive time-bound commandments is not in the Bible, but that doesn't mean in various societal contexts women might have refrained from them.

I love those pictures! Thanks.

"The idea of women being exempt from positive time-bound commandments is not in the Bible, but that doesn't mean in various societal contexts women might have refrained from them."

Drew, your hashkafot - or at least the way you express them, I am afraid, border on being beyond the pale of Orthodox Judaism. It seems as though you do not believe that the torah she be'al peh has the same validity as the written Law. If the gemara learns out a halakhah based on the various "middot sh'hatorah nidreshet bahen" it has the same validity as it would have if it were spelled out in the written Torah. This has tremendous implications, halakhah l'ma'aseh, which as a budding rabbi you should be aware of. Have you discussed your notions of the dicotomy between oral and written Torah with a rebbe of yours? Does he agree with your understanding?

Also, speaking of budding rabbis, in your quasi-halakhic discussion of the issue of teffilin and some other topics, I noticed that you rarely if ever quote or discuss Aharonei Aharonim and modern respons literature. Do you realize the importance of weighing the opinions of poskei doreinu in coming to a pesaq halakhah?

What I've heard about why women shouldn't wear teffilin is that while a person is wearing teffilin, he is supposed to be fully and intensely focused on them for the entire time that he is wearing them. This is almost impossible to achieve, but men continue to put on teffilin anyway because it is a positive mitsva for them to do so, so the fulfillment of the mitsva outweighs the risk of them not being in the right mindset. Since women aren't obligated to fulfill this mitsva, even though they are permitted to, then the risk of them wearing tefillin without being in the proper mindset outweighs the benefit of fulfilling a mitsva which they are not obligated in. I don't remember where I heard this, and I don't know the source or anything - do you?

Anonymous,

I want to make something clear to you that I guess hasn't yet been so: for halakhic purposes, the oral Torah carries a similar, if not greater, weight along with the written one. I do also make note of their distinctions one from another. It's important to not conflate the two, but to rather see them as separate, even though for the halakhic system, that matters little, if any.

No, I have yet to discuss the dichotomy between the oral and written Torahs with rebbeim of mine - I shall certainly inquire.

I am coming into the importance of weighing the opinions of fairly contemporary rabbis, but as I mentioned last week, I see myself as more of a student right now, still trying to learn, rather than a rabbinical student, who is seeking how to posken halakhah as of yet. I think that's what's mainly significant at this juncture which explains the lack of more current, or perhaps, modern (I use this term warily as I

have yet to learn how to distinguish between modern and post-modern, so maybe 'contemporary' may be a better term, though I don't know how far back 'contemporary' will remain a relevant term) rabbinic authorities.

So I will get to that. Nevertheless, in my posting, I do not see what I may have missed - I will be looking into the relevant responsa literature on the topic to see if they have what to add to the conversation.

Jessica,

The answer to your question may be found in the Arukh haShulhan 38:6-7. I may post what is written there.

"I am separating the text of the Humash from the rabbinic interpretations of it - it's how it works."

Um, no, it doesn't. </Orthodox Rabbi>

"If we didn't have midrashim, we would be Karaitic or whatever..."

Actually the Karaim also maintained a belief in the Oral Law to an extent (in this particular, they seem closer to noramtive Jewish thought that you do at this point), they simply rejected those drashos as invalid which took the understanding of a possuk away from the pashtus.

I’d like to take issue on certain matters with both Mr. Ananomous and Drew, but first with Anonomous. There are certainly many levels and ways of interpreting the Torah and this idea is well within the Jewish tradition. The peshat that Drew speaks about and loves has precedence in the Jewish medieval exegetical tradition, although it’s not the use or meaning of peshat as used by the Talmud. The Talmud definitely does not use the term peshat to mean the simple meaning what exactly it means is a argument amongst the rishonim and modern scholars (for good surveys see Halivny and Raphael Loewe). Even Rashi who uses peshat often to mean basically the simple reading, realizes that this was not the gemara’s understanding.

Rashi, Rashbam, and Radak etc. exegetes that I hope u respect and recognize that the rabbi’s understanding of verses are often not the simple reading….They saw that it is valuable to understand this level as a value onto itself and to understand what the rabbis did….which often meant being mechadesh halachot through certain methodologies or midot….The number of midot and the content of them is a subject of disput among the tannaim and amoraim (Hillel 9, R’Yishmael 13, Rabi Yosi Hagalili 32). The rashbam one of the strictest mephorshim of the peshat school recognizes that the halacha and peshat diverge and had no problem with this concept.

On to Drew….I think that you misread the shulchan Aruch in your understanding of guf naki. Guf naki has a very specific meaning in hilchos tefillon. It is referring to the presence and control of bodily functions specifically flatulants. It does not have to do with whether people bathe or wash themselves etc. See Shulchan Aruch 38:2 “Someone for whom it is clear that they will not be able to pray w/o flatulating, it’s better for them to allow the time of prayer to pass than to pray without guf naki. If he sees that he can hold onto a guf naki at the time of shma, then he should wear them, between Ahava and shma and then he should bless”.

The reality is that many women more women than men cannot be as careful or cannot have a guf naki which is required for one who wears tefillon (even a man who cannot maintain a gif naki is exempt).Detrusor (muscle) instability and urinary incontinence is much more prevalent among women then men. These two symotoms are accompanied by flatus incontinence (passing gas). Furthermore, leakage of fecal matter is often linked with these symptoms.(See Eva UF, Gun W, Preben K. Prevalence of urinary and fecal incontinence and symptoms of genital prolapse in women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003 Mar;82(3):280-6. and http://www.thewomenshealthsite.org/article_display.jsp?ArticleID=291).

In this context one can understand part of the motivation of the rabbis like some of the tosefists, the Rema, and many of the achronim. This was an assessment based partly on a physical reality. I will not argue that this was the sole reason for the protest…of course there were the sociological reasons “that’s just not what religios Jewish women should do”, “it’s weird” etc.

In the time of the rishonim it seems that the majority of them are ok with woen wearing tefillon (Rashba, Rashi, R’Tam, Rav Zerahia Halevy) and that sunsequent to the Rema his protest became the norm, although there were always exceptional women and rabbis…..Happy ananomous I’ll give you an Acharon, the Chief rabbi of Jerusalem and his son in the 18th century R. Yisrael Ya'aqob Alghazi and his son R. Yomtob Alghazi.

I think that this issue is complicated (I’m not poskiming halacha), just sharing my thoughts on the issue…..If women really feel that it can help them in their avodat Hashem (service of Hashem), “Why not let them”? They can try to be zrizut in guf naki just like men….For women who are shomer mitsvot and driven to this mitsva then I guess that it can be worth the “hardship” or challenge. (Women also may choose to ignore halacha and not be zrizut which I obviously would not recommend).

However, there are complicating factors, like where and what communities a women does it in. One should be careful that it is not seen as Yahora (showing off) and be mindful of both the men and women in the shul (I’ve heard women say that it makes them feel like bedieved jews etc. in the presence of such women in shul). Obviously with time, if this practice becomes more common then the aforementioned issues and other sociological will melt away in certain communities.

Oh yeah, don’t one should also mention the targum Yonatan Tachshit (tefillon seen as a kli gever), although this seems to be a non-issue in terms of halacha for the rishonim many of the achronim. However, one should consider how in modern times this idea resonates for many orthodox Jews for sociological reasons.

Your first interpretation of the Rema is silly....peshat may be along the lines of the Magen Avraham whosays that women will not be zrizut b/c they are not obligated in the mitzva and will therfore treat it more lightly.

Also, I agree with you taht the torah no where elucidates the concept that women are exempt from time bound commandments, but the Torah according to a peshat level encourages one to only teach men to wear talit and tefillon..."And u shall teach them to your sons" (devarim 11:19 and this is if u assume totafot and my words are refering to tefillon).

This is not the drasha of the gemara which says that this teaching (ulimadtem otam) is a commandment of a father to teach his son Torah and a hekesh (an interpretation based on juxtaposition) is made in between Torah learning and tefillon to exempt women from these mitsvot (kiddushin 20a).... but my peshat is still a "cute" read in my mind.

Sorry kiddushin 34a

No attempt at all to define "cleanliness"??? This was a HUGE issue of debate in the middle ages and you totally gloss over it as if it is some vague term that doesn't apply to women!

This analysis is very, very lacking.

Here's a starting point for you: Why don't men wear tefillin all day long?

rabbi gil,

is that you? did you wake up on the obnoxious side of the bed this morning? you've got to know a better way to phrase your point

Sorry about the tone.

Quoting Gatos Hombre:

"Rashi, Rashbam, and Radak etc. exegetes that I hope u respect and recognize that the rabbi’s understanding of verses are often not the simple reading…"

Yes, of course I recognize that. I am aware of quite a few biblical exegetes. Your bringing this up, however, elucidates my point that Drew had posted a semi-halakhic opinion (even if he wasn't trying to "pasken" per se), and in the context of paskening halakha - which as a rabbi Drew will no doubt do - one must follow a certain system of rules. Certainly there is tremendous value in learning peshat, but pesaq halkhah is NOT about looking up what the Ibn Ezra, RaDa"Q, or anyone else said about such and such a pasuq and then trying to come up with a halakhic opinion based on that. I would hope you recognize that.

"If women really feel that it can help them in their avodat Hashem (service of Hashem), “Why not let them”?"

My response would be that one (man or woman) must strive to follow halakhah, as determined by those who are qualified to do so. If a woman asks a poseq whether she should wear tefillin or not, and the poseq says that the halakhah is such that a woman should refrain from wearing tefillin, then that's what she must do. There are many things that, as observant Jews, we want to do, even things that will "help us in our avodat Hashem" but that we can't do because our ultimate goal is to follow halakha. Following the halkhah IS our avodat Hashem. If someone feels they "must" do something to "better fulfill avodat Hashem" they are probably confusing true avodat Hashem with simple self-fulfillment.

GH,

It's funny, because, like many other guys, I've been under the impression that women are less likely to pass gas than guys (if not thinking that they never fart). Thus, it strikes me as peculiar that not only are women as likely, but more likely than fellas to break wind.

Hey Gil,

Well, as a "starting point", I had been under the impression that it was due to not being able to keep sexual thoughts about the ladies at bay. But maybe you can disprove me.

Anon (aka Mr. Pop-Off),

(warning: polemical language to follow) Man, whence is your sense of halakhah being equated with avodat haShem? These are two separate concepts - check it, they're not.

For starters (not to paraphrase Gil), avodat haShem is a much more expansive concept than is adherence or following of halakhah (or, maybe for you, it would be Halakhah).

"probably confusing true avodat Hashem with simple self-fulfillment" - or, maybe not, maybe they want to perform מצות.

"There are many things that, as observant Jews, we want to do, even things that will 'help us in our avodat Hashem' but that we can't do because our ultimate goal is to follow halakha." If one wants to steal and thinks that is part of their avodat haShem, they're clearly wrong. If one wants to do a מצוה, it's not that they cannot do it, and it's not quite against halakhah, per se.

"Here's a starting point for you: Why don't men wear tefillin all day long?"

Actually, as I imagine you are aware, some men do wear tephillin all day long; in fact, if I'm not mistaken Maimonides does not really differentiate between wearing it for prayer and wearing it throughout the day. Do you have any sources (preferably Tannaic or Amoraic ones) to support a claim that men should not/must not wear it all day long? (And let us, in argumentation, carefully differentiate between oughts and musts)

Alan, that's precisely the point

Gil,

So, you're just admitting to Alan like that that you have no sources to back yourself up?

this is a very interesting discussion, though it often veers dangerously off the path of proper Jewish law. i don't know if this blog is still kept up but it would be VERY beneficial to its readers to take a look at the new book on the 13 Principles of Faith by the Rambam that was explained and studied very thoroughly, published by www.KolMenachem.com. They even have a sample of lessons that would definitely be worth your while.

Rachel,

Yes, this blog is still kept up, although I don't know how many people may still be reading this post (or, for that matter, the blog as a whole...).

While I do agree with you that it "is a very interesting discussion", I do not see how it, as you put it, "often veers dangerously off the path of proper Jewish law." This is the body of the discussion - we are talking about "proper" Jewish law.

Nevertheless, the Chabad book you are suggesting may offer one take, but Chabad does not have a monopoly on Jewish law and thought.

If you don't mind my two cents, here they are: If a woman is going to put on tefillin, she should also be wearing a tallit katan and a tallit gadol (per Minhag Ashkenaz that one starts wearing a tallit gadol at the beginning of adulthood). Furthermore, they should fulfill all of the other time-bound mitzvot which are possible for women to fill in the modern era (e.g. nothing to do with korbanot). Furthermore, I suspect that even in this case, it would be inadvisable to wear tefillin during niddah, due to the concerns of the Mechaber and the Rema in regards to having a clean body.

Post a Comment